I’ve never been a fan of state nicknames. They are generally unremarkable and, to be frank, feel like they’re pushing the boundaries of reality. How much have I learned from Rhode Island’s nickname of The Ocean State? And what about West Virginia’s The Mountain State. You aren’t fooling anyone with those hills, West Virginia.

At best state nicknames are just misinformation.

State mottos I understand. Massachusetts’s “Sic Semper Tyrannis” is commendable and might even help balance out for their accent. Dead languages add a certain credibility to most things.

Montana’s nickname is an exception to the rule. Big Sky Country is an idea that has always intrigued me. How can the sky be bigger over yonder than over hither? Why would the sky look bigger when there are more things (mountains, presumably) to block the view?

I grew up in the Midwest. If you haven’t been there, trust me, there’s not much to block the sky in those parts. It is so featureless, many motorists opt to careen off the highway and into the ditch instead of suffering another 350 miles of corn and soybeans. Anything to feel alive again, you know? So why is the sky so much bigger in Montana?

Google isn’t very useful here. Evidently the nickname came from an ad campaign in the 60’s and was a reference to “the unobstructed skyline in the state that seems to overwhelm the landscape.” Other bloggers have asked the same question but seem fine with leaving it unanswered or relegating it to some sort of subjective feeling they have when gazing upon the majestic vista overlooking the blah blah blah.

Don’t fret, dear readers, for I will deliver. And I really don’t think it is that complicated. The Big Sky is caused by two complimentary phenomena: 1) With lots of local relief (elevation differential) you can see over obstacles and 2) humans use visual cues to judge scale at distance.

It seems that because the Midwest is as flat as a strip mall parking lot, the relatively short things like trees and buildings are enough to block a lot of the sky. Without hills or mountains or valleys or ravines there are no vantage points to see over these things. You rarely get a clear view of the Steak n’ Shake, let alone the horizon.

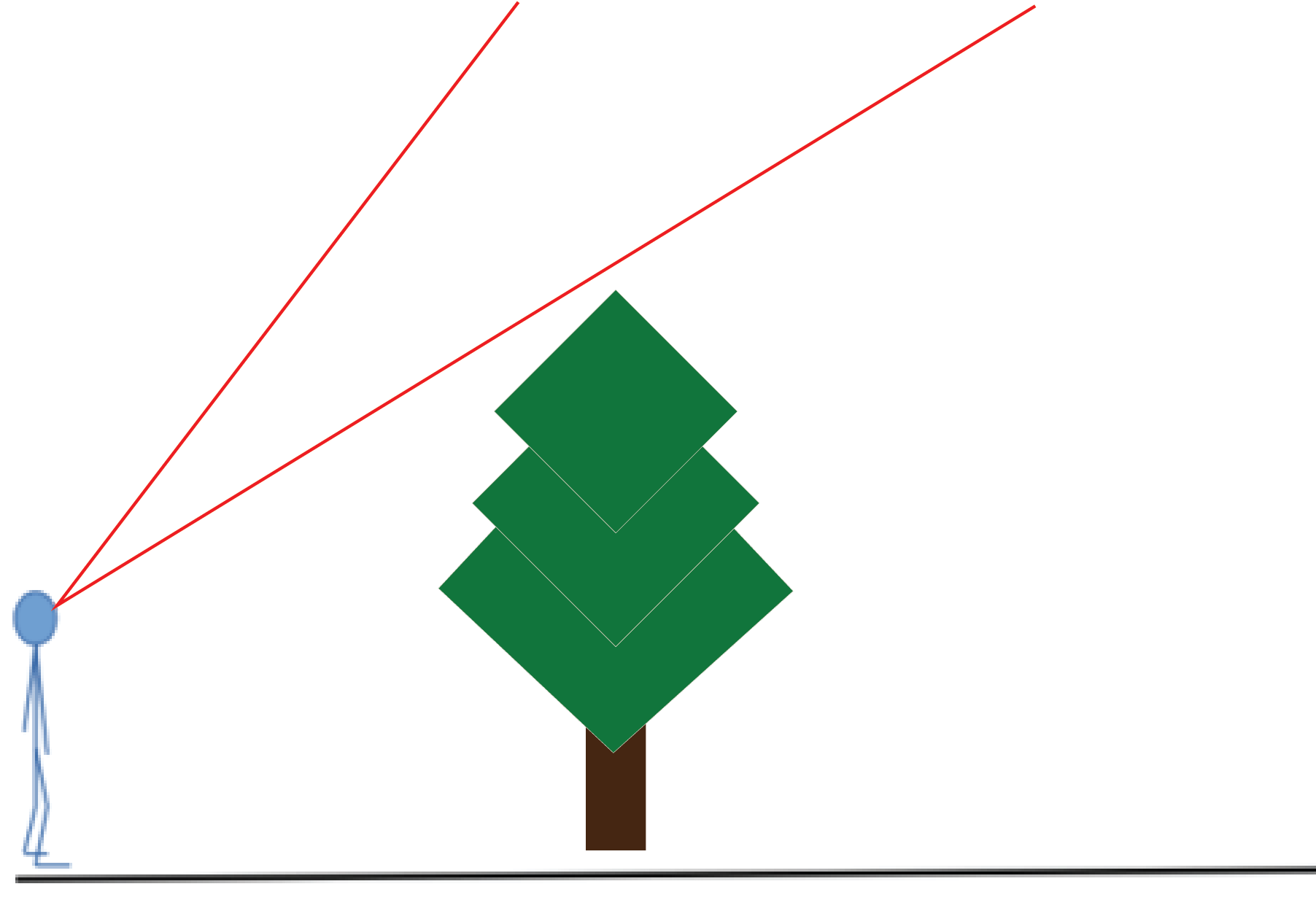

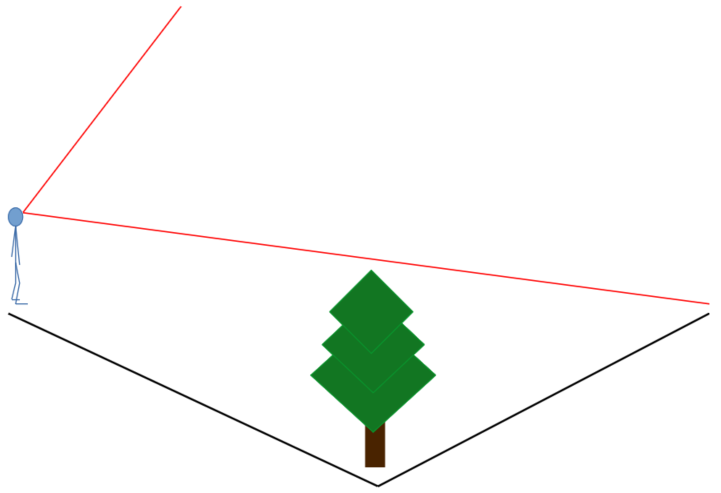

Below are two images that illustrate the point. While I don’t think they help much, I spent far too much time on them not to show them. You must see them at this point.

The complimentary phenomenon to local relief is how we judge scale. Have you ever looked at the clouds from an airplane window seat? How many feet across is any given cloud below you? In the following image how many feet below the aircraft are the clouds?

From this vantage point the ability of our minds to judge distance and scale is hampered. When we look at the sky in the Midwest there is nothing to provide context except the relatively small distances we can see.

When we look at the sky in a mountainous place like Montana, we see things that help us judge scale. Because the mountains and cliffs and trees are out there, the scale of the distant sky is given context and perceived at the appropriate large scale.

Check out this Google Street View image from the town where I was born:

And this image from somewhere between Helena and Bozeman, MT:

The horizon lines in both images are roughly halfway up the height of the image yet the difference in perceived scale is clear. Almost like a mirror, the bottom half in the second image is clearly a great distance so we also see the sky as having a great distance.

In the future, I’ll use the power of GIS and attempt to quantify this theory. I use the word “theory” in the colloquial sense. In truth, it is probably just an idea. Perhaps one day through hard work and honesty, that idea will grow up and achieve its goals. Or perhaps it will dream about becoming a theory but never act… continually telling itself “someday, someday I’ll become a theory.” But someday, well, someday never comes.

John Tillery says:

Makes perfect sense to me. Good luck on the “Theory”…

tlutgen says:

I think your photos drive the point home pretty well – nicely done.

as for your IDEA becoming a theory, it can be better expressed In schoolhouse rock fashion…

“…But I know I’ll be a Theory someday, at least I hope and pray that I will, but today I am still Just an idea.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FFroMQlKiag

stephen hudak says:

It’s a long, long wait while my idea sitting in committee, so in the meantime, I’ve been getting Part 2 ready with some GIS-derived evidence.

Andrea says:

This post was a delight to read! i also believed the big sky phenomenon had something to do with humidity (or lack thereof). I am weighing in from Alberta (the province just north of Montana) and people have casually assumed the big sky nickname here too, at least between the other canadian provinces. The air is really dry, especially around the rocky mountains, and i thought maybe the lack of moisture creates a ~crispness~ effect that makes the clouds stand out more and distort the perception of their proximity. sunsets are often times surreal looking here…

anyways thanks again for a fun post.

Kyle says:

Thanks for the greaT explanation and the imaGes to illustrate tHe ideas! Driving through MonTana right now, this is definitely the best eXplanation i’ve Read.